The challenges of Ebola

2019: the current epidemic

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is in the midst of an Ebola epidemic, the second-worst this century. Now with over 3100 confirmed cases of Ebola and more than 2000 deaths, health workers and rapid response teams face new challenges. This comes just a short time after the 2014-16 Ebola epidemics in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, which claimed over 11,000 lives.

In order to get to grips with the current crisis, we spoke to Neil Bentley OBE, a Biomedical Scientist and Head of Technical Services for the National Infection Service at Public Health England. His role in setting up laboratories and diagnostic services in Sierra Leone in 2014 gives him a unique vantage point and can help us to understand some of the difficulties about the current situation in the DRC.

What are your thoughts on the Ebola epidemic in the DRC?

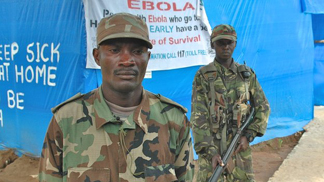

“The DRC is in the middle of a civil war, and whilst this is happening Rapid Response Teams (RST) are working with doctors, nurses, organisations and charities to help resolve this current epidemic. I am not currently involved with the RST initiatives but on speaking to colleagues that are, it sounds as though security is difficult and is a major obstacle to enable wide-scale deployments. A colleague of mine working for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported one situation where armed men were firing RPG rounds at their hotel, and she hid in the bath for three to four hours until the shooting stopped.

Our RST has deployed to DRC 11 times since August last year, and that team includes data scientists, epidemiologists, infection control specialists and research nurses. At present we have been advised that there is not a need for additional laboratories. There are also issues with language and those on the RST with a working knowledge of Portuguese are like gold dust.”

What do you think Rapid Response Teams should keep in mind when handling epidemics?

“My advice would be to embrace the local culture. Health and safety are paramount, but the most important person out there is you. This is what I told those that were deployed in the West Africa outbreak.

Furthermore, I would add that whatever your expectation is, halve it. It’s unlikely that you will see patients and action. Most of what we do is in the confines of the “self-controlled” laboratory or healthcare setting. You think you’re going in there to save the world but the chances are you won’t see an Ebola patient, you’ll see a blood sample. If you’re in a lab that’s not associated with an Ebola treatment centre, you have to accept what you’re going out there for. At the end of the day everyone is working together to help save lives.”

How can people help?

“Although it’s difficult to help with the current circumstances there are a number of things we as scientists can do. We could donate time, knowledge or funds to governing bodies and charities like World Health Organisation (WHO) and MSF. As scientists we can raise awareness that this epidemic is a worldwide problem, and has been declared a public health emergency by the WHO.

The outbreak is now the second-largest ever and is following a very similar path to the largest in West Africa in 2014. There are good laboratories set up in the DRC but the problems teams will face are the same we encountered in 2014; issues with the armed conflict and supply chain. People who want to help could work on how to make the supply chain more efficient and scientists could look to develop diagnostic assays that don’t require a cold chain by the use of ambient or freeze dyed reagents.

When I was in Sierra Leone, the local government closed the schools down, which meant no teaching of children for almost two years. They taught lessons over the radio. Everyone can help in a small way, mainly through donations. People can donate money so the local people can buy radios. Donations of books or telephones would help, as well as any old clothing. People are walking around with very little, so any donations like football shirts, old bras, and shoes would be appreciated.

I am currently working with Anglia Ruskin University students to develop WhatsApp videos that teach basic health and safety and food preparation techniques. These videos will show how to clean a chicken, how to wash hands properly, as well as share public health messaging. What struck me was that even in the poorest countries, everyone has a phone.”

Looking back to 2014: Ebola in Sierra Leone

In 2014, the world witnessed the worst Ebola outbreak in our history. In Sierra Leone over 450 staff were deployed from the UK with just 50 scientists in the country at any one time. These scientists served three field laboratories under the leadership of Neil Bentley OBE. Five years later, Neil recollected his experience dealing with an Ebola epidemic.

What challenges did you encounter?

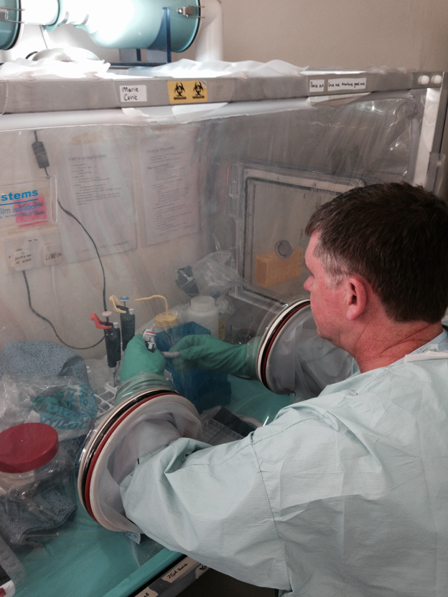

“I was there off and on for about a year, between 2014-16. My remit was to commission laboratories at three sites across the country that were built by the British Military outside high population areas. Our role, once signed over to us was to set them up with the team to run diagnostic services for malaria and Ebola. Within the Kerrytown laboratory we worked alongside British military scientists who provided a field pathology service on top of our disease screening service. We had to get the supply chains working quickly, and needed to liaise with national and local government to get effective sample transport logistics in place.”

There are quite a lot of chiefdoms out in Sierra Leone, and many of the local people didn’t trust us as we were outsiders, with some actually thinking that we carried the disease and had deliberately infected them. We experienced elements of that, like when some locals showed that we were not welcome by throwing rocks at our transport, and it was clear that it was not a place to stop without military support. This was a major concern and because of the fear and distrust, many infected people didn’t go to treatment centres and instead stayed at home. As a result these people didn’t get isolation and treatment and frequently passed the disease onto their close friends and families.

We faced issues with the supply chain as well, as logistical problems could hold up any operation. We learned that, for example, temperature-controlled reagents requiring continued cold chain were frequently sat on the runway awaiting import paperwork for 24-48 hours in 40C heat, rendering them useless. Additionally, in many instances, clinical samples were batched up at the Ebola holding centres and not sent to laboratories for analysis because the locals had no petrol or mechanisms of transport.

Raising public health awareness was of paramount importance, so once our team got the laboratories up and running, we focused on working with Local and British Governments to allow import licences to be waivered, on getting the locals petrol to get the samples to hospital, training people on how to label samples properly, and building relationships with the local people.

Thanks to our team’s efforts, we improved the turnaround time from 4-5 days to less than 24 hours in 95% of the time.

Because you’re in a high-pressure situation, you’re only as strong as your weakest person. I wasn’t ever scared of catching Ebola as I know about the virus and how to prevent transmission and how to stay safe. There was a need to look after staff welfare at work and if there was anyone who showed signs of stress or unease we removed them from the lab for safety reasons. We then assigned them a job outside the lab for the remainder of their deployment.

The scariest thing for me was the roads. Many are treacherous and travelling by night is frightening, as it’s pitch black and sometimes it’s just a dirt path with vehicles being stopped and people sleeping rough. It’s not a safe area to be in at night. The most traumatic thing I saw was a person, who had likely died of Ebola, thrown out of a moving vehicle because the people with him didn’t know what else to do. It was a frightening time.

What helped our team improve relations with the locals was adopting their culture and building relationships. For example, the locals had a tradition known as Friday dress, where you wore African-style loud shirts. We got some of these shirts, and they helped us become accepted into the community by making that simple statement.

We also wanted to engage with the local community officials and government, such as the village chieftains and witchdoctors. If you can convince them that you’re not trying to infect them, they can then pass the message on to the villagers as they have high standing and are listened to. This was especially important in rural areas like Port Loco, and we had to be mindful that our way wasn’t the only way; we had to look past our cultural differences and work with them to stop the infection spreading.

You have to appreciate where people are coming from and their traditions. We know that the bats are a prime carrier of the Ebola virus. However, bat soup is a delicacy in Sierra Leone. You can’t tell the local people not to eat them. The same goes with bush meat. When people are living in shanty towns and jungle villages and are living off of food they catch, you’ve got to work out a way of catching, killing and cooking the food safely to avoid the Ebola virus. It’s not a case of ‘trust us, we know best’. They know best. We just need to help them do what they are going to do anyway in a safer manner.”

Would you go ever back?

“In a heartbeat. The best thing I saw was when someone came out of the Ebola treatment centre cured of disease, they’d dip their hand in paint and make a handprint on the wall. When more and more handprints went on the wall, it was very rewarding. You could see you were making a difference.”

In 2016 Neil was awarded an OBE for his efforts.